TRACKLIST

A1 Kenji Endo– Curry Rice

A2 Kazuhiko Yamahira & The Sherman– Sotto Futari De

A3 Sachiko Kanenobu– Anata Kara Toku E

A4 Fluid*– Rokudenashi

A5 Kazuhiko Kato– Arthur Hakase No Jinriki Hikouki

B1 Happy End– Natsu Nandesu

B2 Takashi Nishioka– Man-in No Ki

B3 Masato Minami– Yoru Wo Kugurinukeru Made

B4 Maki Asakawa– Konna Fu Ni Sugite Iku No Nara

B5 Fumio Nunoya– Mizu Tamari

C1 Haruomi Hosono– Boku Wa Chotto

C2 Takuro Yoshida– Aoi Natsu

C3 Akai Tori– Takeda No Komori Uta

C4 Gu (4)– Marianne

C5 Tetsuo Saito– Ware Ware Wa

D1 Gypsy Blood*– Sugishi Hi Wo Mitsumete

D2 Hachimitsu Pie*– Hei No Ue De

D3 Ryo Kagawa– Zeni No Kouryouryoku Ni Tsuite

D4 The Dylan II– Otokorashiitte Wakaru Kai

DESCRIPTION

First-ever fully licensed compilation of this music to be released outside Japan

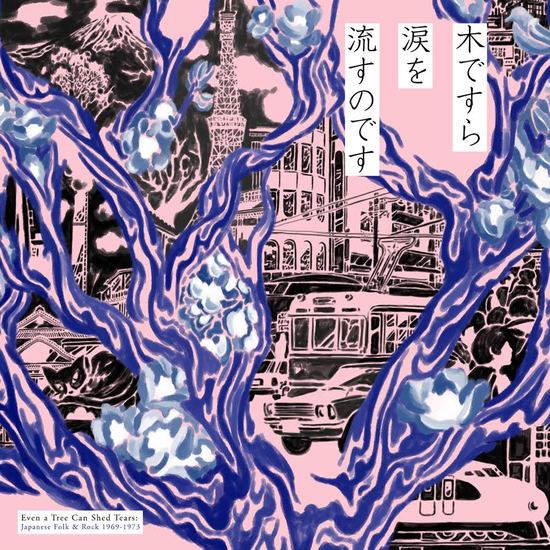

Original artwork by illustrator Heisuke Kitazawa

Includes book with extensive liner notes and bios by Yosuke Kitazawa and Jake Orrall

Compiled and produced by Jake Orrall, Yosuke Kitazawa, Matt Sullivan, and Patrick McCarthy

There was something in the air in the urban corners of late ‘60s Japan. Student protests and a rising youth culture gave way to the angura (short for “underground) movement that thrived on subverting traditions of the post-war years. Rejection of the Beatlemania-inspired Group Sounds and the squeaky clean College Folk movements led the rise of what came to be known in Japan as “New Music,” where authenticity mattered more than replicating the sounds of their idols.

Some of the most influential figures in Japanese pop music emerged from this vital period, yet very little of their work has ever been released or heard outside of Japan, until now. Light In The Attic is thrilled to present Even a Tree Can Shed Tears, the inaugural release in the label’s Japan Archival Series. This is the first-ever, fully licensed collection of essential Japanese folk and rock songs from the peak years of the angura movement to reach Western audiences.

In mid-to-late 1960s Tokyo, young musicians and college students were drawn to Shibuya’s Dogenzaka district for the jazz and rock kissas, or cafes, that dotted its winding hilly streets. Some of these spaces doubled as performance venues, providing a stage for local regulars like Hachimitsu Pie with their The Band-like ragged Americana, Tetsuo Saito with his spacey philosophical folk, and the influential Happy End, who successfully married the unique cadences of the Japanese language to the rhythms of the American West Coast. For many years Dogenzaka remained a center of the city’s “New Music” scene.

Meanwhile a different kind of music subculture was beginning to emerge in the Kansai region around Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe. Far more political than their eastern counterparts, many of the Kansai-based “underground” artists began in the realm of protest folk music. They include Takashi Nishioka and his progressive folk collective Itsutsu No Akai Fuusen, the “Japanese Joni Mitchell” Sachiko Kanenobu, and The Dylan II, whose members ran The Dylan cafe in Osaka, which became a hub for the scene.

Even a Tree Can Shed Tears also includes the bluesy avant-garde stylings of Maki Asakawa, future Sadistic Mika Band founder Kazuhiko Kato with his fuzzy, progressive psychedelia, the beatnik acid folk of Masato Minami, and the intimate living room folk of Kenji Endo.

Nearly 50 years on, this “New Music” is born anew.